Me, Mel Robbins, And The Triangle Of Doom

Last Wednesday, I was in the studio about to go live to thousands of people to deliver the virtual keynote address for a Fortune 50 company’s global World Mental Health Day event. I was excited. Killing time, the video producer and I got to talking. He said, “I produced Mel Robbins last year. She was amazing.”

I felt a familiar feeling. My heart started racing and my stomach sank. “Not again,” I thought. But, determined to be curious and adopt a growth mindset, I asked the producer, “Why was she amazing?” He proceeded to tell me how she has the gift of understanding people, putting our universal feelings into words, and captivating an audience. “She’s hilarious, and her energy is just… amazing,” he said.

And as I sat in my chair, ready to go live and try to captivate my own audience, I was seized by anxiety. Yet again, someone was bringing up Mel Robbins and talking about how amazing she was. And I thought, surely, if she is so amazing, so famous—dominating the bestseller lists, selling out arenas, and filling all my friends’ Instagram feeds—then I, a small speck in the universe of people who talk and get paid for it, must be the opposite of amazing. Who do I think I am?

For five minutes after my chat with the producer, I sat there feeling awful. My energy plummeted, my mind spiraled, and I ruminated about Mel. Then it was time to go live. Because I’m a pro, I did my energetic breathing, the show went live, and I did a good job. But I have a bad case of the Mel Robbins.

At least once a week, someone brings up Mel Robbins to me. Some even say, “You should be more like Mel.” For a long time, I couldn’t bring myself to watch her videos—it made me feel terrible about myself.

I think people mention Mel because, like her, I talk about the power of emotions, why understanding your feelings makes you strong, why anxiety is a common traveler in life and leadership. I’m frank and personal. But clearly, I’m no Mel Robbins. She’s a phenomenon, and a generational talent (and Mel Robbins if by any chance you read this- hello!)

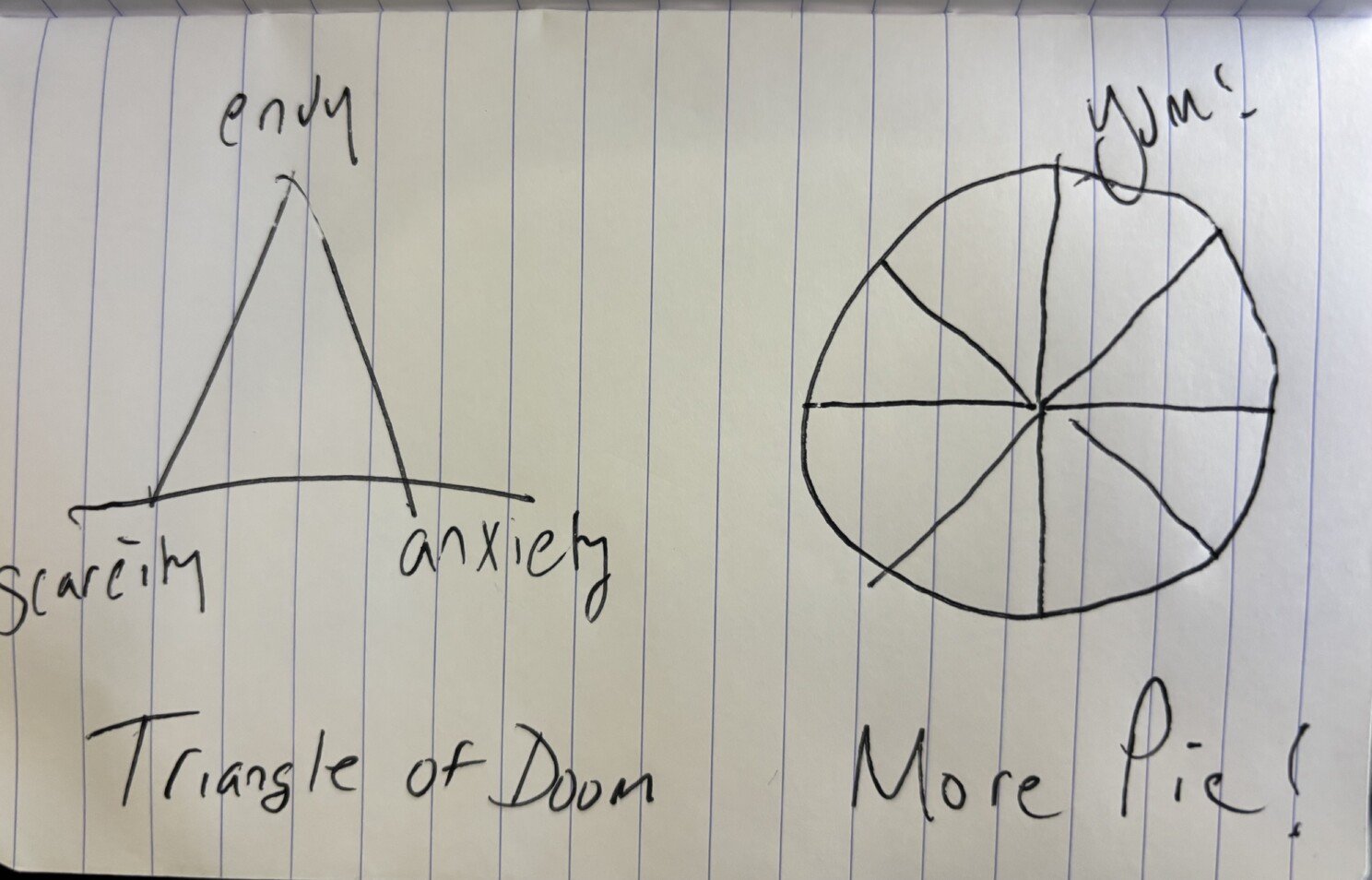

And honestly, I’m okay with that. I don’t want to pack arenas; I love my life. I admire her impact (and I’m sure her income is nothing to sneeze at), but I don’t want to be her. Still, I find myself experiencing very strong feelings when her name is mentioned, and my mood always plummets. When people tell me I should be more like Mel Robbins, I plunge into what I call the triangle of doom: three emotions that often travel together—envy, anxiety, and scarcity.

These feelings can drive so many of us into a perpetually anxious state. Whether we’re self-employed or trying to climb inside an organization, envy is a natural human emotion. What’s worse, many of us operate in a digital and professional landscape literally designed to amplify jealousy and FOMO.

The dictionary defines envy as “a feeling of discontented or resentful longing aroused by someone else’s possessions, qualities, or luck.”

I don’t think we should ignore or deny these feelings, as uncomfortable as they are. Instead, we should look at them, interrogate them, and ask: Are you trying to tell me something, or should I let you go?

Because if you let envy run unchecked, it can wreak havoc on your focus, confidence, and creativity. When I interviewed Beekman 1802 co-founder Josh Kilmer-Purcell, he shared his own battles with envy and offered this reframe: “Don’t be envious of their success—try to figure out what created that success and what part of it you can apply to what you’re working on. Don’t copy them. Learn from them.” It’s the reframe from “What’s wrong with me?” to “What can I learn??

For me, that reframe became a mantra: more pie. It sounds silly, but every time I feel scarcity—when I start to believe there’s not enough to go around—I see a yummy pie in my head and I remind myself, there’s always more pie. There is room for me, Mel Robbins, and everyone else in this world! It’s my way of breaking free from the triangle of doom.

Still, envy is tricky. It’s a painful emotion, and we don’t like to admit we feel it. I brought the topic to Tanya Menon Professor of Management and Human Resources at Ohio State University, who has spent years studying envy in the workplace. Listen to our interview here.

“Envy is something psychologists tend to avoid,” she told me. “It’s one of the seven deadly sins. It’s fascinating, but it’s painful and dramatic.” Her research shows that envy narrows our attention, turning our minds into microscopes that zoom in on tiny, meaningless differences: who got more likes, who got promoted first, who was invited to that meeting. “It makes us small,” she said. “The question to ask yourself is: Is this emotion making me a smaller person or a bigger one?”

Menon said she sees envy and anxiety as close cousins: both rooted in uncertainty, both thriving when we feel insecure about our place in the world. “People who are more anxious and more worried experience more envy,” she told me. “If people are secure, envy doesn’t manifest as much.”

That line—if people are secure— is key. We live in an era where insecurity is the air we breathe. I just learned of the term “job hugging,” in which people right now will not let go of their jobs at any cost, because it’s so hard to get a new one. So no wonder envy runs rampant.

Envy shows up differently for everyone. It can look like constant comparison, criticism of others, or a fixation on “fairness.” It can make us quietly root against colleagues we actually like. But underneath, Menon says, it’s often just fear: What will happen to me if I don’t get what they have?

So how do we stop envy from taking over? Menon says the first step is awareness. Most of us don’t even admit we feel envy; we rationalize it away. “We say, ‘That person just got lucky,’ or ‘Their work wasn’t that good,’ instead of acknowledging our own envy,” she said. “That’s what makes it so hard to learn from it.”

Instead, she suggests naming the emotion—without shame—and setting internal boundaries. “Envy is a boundary-setting exercise,” she explained. “It’s about controlling your own gaze. Instead of fixating on what others have, focus on your own goals and standards.”

In a way, she’s describing emotional hygiene. Just as we keep germs out with clean hands, we can keep envy from festering by protecting what we let into our mental space.

When we’re anxious or depressed, we ruminate. “We stay on the tennis court rehashing the missed serve,” she said. “It’s about learning to leave the court.” Leaving the court might mean muting that group chat, unfollowing a few people on LinkedIn, or simply turning off your phone for the evening. It’s not about denial—it’s about giving your nervous system room to reset. She also reminds us: envy often signals what we value. “Envy can point to what’s important to us,” she told me. “It’s a clue.”

That insight leads to the next question: What can I do with that clue? That’s where my friend, executive coach Nihar Chhaya, MBA, MCC comes in. Nihar and I have often talked about how envy, anxiety, and scarcity reinforce one another—a self-perpetuating “triangle of doom.” When you’re anxious, you’re more prone to envy; when you’re envious, you feel scarcity; and when you feel scarcity, you get anxious again. Listen to my interview with Nihar here.

For entrepreneurs, solopreneurs, and high achievers, that loop can feel endless. “If you’re feeling behind or uncertain, you’re more susceptible to cues of what others are doing,” Nihar said. “And that’s when you start thinking, ‘How do I stand out? How do I make sure I’m not falling behind?’” Sound familiar?

Like Menon, Nihar believes envy can be instructive. “When you start envying something, it’s often a signal of what you deeply value,” he said. “It’s pointing to a part of you that wants to grow.”

His advice? Take a sabbatical from your triggers. “Unfollow, mute, or take a break from the sources that set you off,” he said. “Replace that time with creating something of your own. Don’t measure your work before you’ve even done it.” So many of us anxious achievers are experts at pre-disappointment. We edit ourselves before the world even gets a chance. We assume the pie is already gone, but it’s not. Here’s how to start shifting your own triangle of doom:

Name it. When you feel that rush of envy, anxiety, or scarcity, say it out loud—or write it down. Labeling interrupts the automatic spiral.

Get curious. Ask: What is this feeling telling me? Maybe it’s pointing to a value—creativity, autonomy, recognition—that needs more space in your life.

Reframe it. Move from comparison to curiosity: What can I learn from this person instead of resenting them?

Set boundaries. Protect your attention. Limit exposure to triggers, social media, or conversations that shrink you.

Practice “more pie.” Say it until you believe it. There’s always more opportunity, more ideas, more ways to make meaning.

Shift your focus outward. Amplify someone else’s success. Comment, share, or send a congratulatory note. It’s a small act of generosity that rewires the brain toward abundance.

As I write this, I’m still thinking about that producer’s comment about Mel Robbins. It’s not the first time I’ve felt envy, and it won’t be the last. But instead of shrinking, I’m trying to remind myself there’s enough room for both of us. There’s enough room for you, too.

When you feel caught in the triangle of doom, pause. Breathe. Ask yourself: Is this emotion making me smaller—or bigger? And then remind yourself: there’s always more pie.

Morra

P.S.: I loved this piece from former Netflix Chief Talent Officer Jessica Neal on how we’re “rewiring our brains for burnout.” She writes, “At Netflix we didn’t celebrate wins!” Worth a read.